Children don’t start reading just by memorizing letters. They build language from the ground up—by listening, moving, speaking, and touching. The Montessori method understands this. It doesn’t rush the process. Instead, it carefully prepares the child’s environment and experiences, so reading and writing grow naturally, with joy and confidence.

For parents and educators, knowing what research says about Montessori’s literacy model helps build trust in the process. While it may look different from traditional phonics drills or early readers, the outcomes often speak for themselves.

What Makes Montessori Literacy Unique

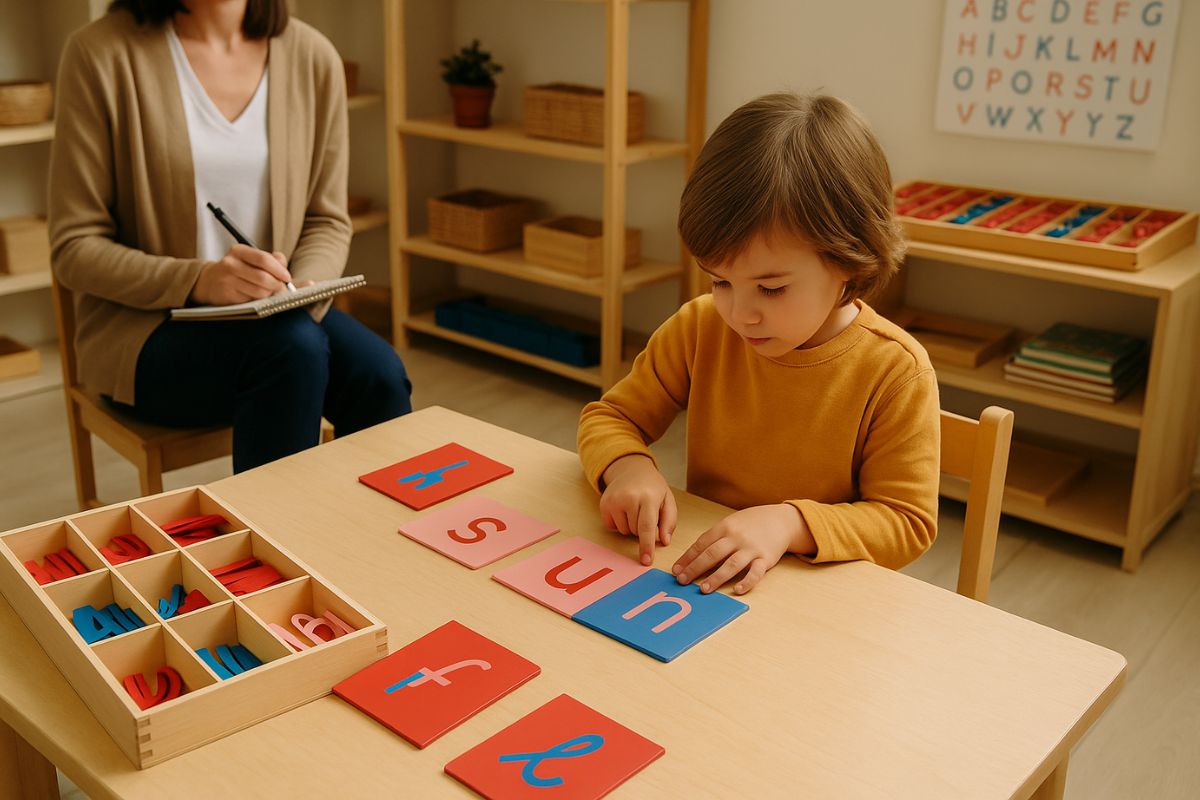

Montessori literacy begins well before a child reads their first word. It starts with sound games, rich vocabulary, and fine motor practice. Language work is woven into every part of the classroom—from storytelling and matching objects to sandpaper letters and moveable alphabets.

The process is multisensory and sequential. Each activity builds on the next. Children hear the sounds, trace the shapes, say the word, and eventually write and read. There’s no rush to books. The focus is on building internal understanding first.

Key Features of the Montessori Literacy Approach

Montessori classrooms offer tools that isolate difficulty and allow repetition. For example, sandpaper letters let children feel the shape of each letter while saying its sound. This builds muscle memory and phonemic awareness at the same time.

The moveable alphabet allows children to write words before they’ve mastered handwriting. This bridges oral language and written expression without the frustration of pencil control.

Objects, cards, and labels are all used to help children link spoken and written language. The materials are concrete, inviting, and purposefully designed.

What the Research Tells Us

Studies on Montessori literacy are growing. A 2006 study by Lillard and Else-Quest found that Montessori students in early elementary had stronger reading and math outcomes than their peers in conventional schools. More recent research supports the idea that Montessori helps children develop phonological awareness, vocabulary, and early writing skills.

Montessori children tend to score well on decoding, spelling, and reading comprehension tasks. This success is tied to the way phonics is embedded in hands-on learning, not taught as an isolated skill.

Children also show strong motivation and confidence in their reading journeys. They often enjoy reading because they feel ownership over it.

Phonemic Awareness: A Strong Foundation

Before reading words, children must understand the sounds within them. Montessori uses daily sound games—”I Spy” with beginning, middle, or ending sounds—to tune children’s ears to language.

Research in early literacy points to phonemic awareness as a powerful predictor of reading success. Montessori supports this skill with fun, interactive activities long before formal lessons begin.

By the time children use sandpaper letters or build words with the moveable alphabet, they already have a rich sense of how sounds work in spoken language.

Writing Before Reading

In Montessori, children often write before they read. This might seem backward, but it makes sense developmentally. Writing, especially with the moveable alphabet, lets children encode words they already know how to say.

They don’t need to decode unknown print yet. They just need to break down their own speech into sounds and build it back with letters. This empowers children and gives them a real purpose for using symbols.

Once they’ve built many words and sentences this way, reading follows naturally. The print becomes familiar. The logic clicks into place.

Reading as a Personal Discovery

Montessori reading happens at a personal pace. There are no assigned readers or levels. Children choose texts that interest them. They might read labels around the room, word lists, or small books created with the teacher’s help.

This freedom increases engagement. Children read because they want to understand or find out something—not to check a box or pass a test.

Teachers track progress closely, offering support and introducing new materials when a child is ready. But the process is led by the child’s own curiosity and interest.

Real-Life Language Matters

Montessori emphasizes meaningful communication. Children write messages, label their environment, and share stories with others. This gives literacy a real-world purpose.

Instead of random worksheets or artificial word lists, children use language in context. They write birthday invitations, signs for a classroom garden, or a letter to a classmate. Reading and writing feel relevant, not abstract.

Studies show that children are more motivated to read and write when the tasks have personal or social meaning. Montessori builds this into the daily routine.

A Calm and Focused Environment

Montessori classrooms are known for their peaceful atmosphere. This calm helps children concentrate, which is vital for literacy development. Reading requires sustained attention and interest.

There are no loud distractions or timed tests. Children can spend ten minutes working with a new book or thirty minutes writing a story. They are not rushed, compared, or corrected harshly. This safety allows for deeper focus and steady progress.

The Role of the Adult

In Montessori, teachers observe closely and step in with targeted guidance. They offer three-period lessons, introduce new sounds and materials, and answer questions with care.

They don’t dominate the learning. Instead, they prepare the environment and give children tools to succeed on their own. This respect for the child’s timing and process builds confidence and independence.

The adult also models a love of reading. By reading aloud regularly, using thoughtful language, and sharing books, they show children that literacy is not a task—it’s a gift.

Literacy Across the Curriculum

Montessori doesn’t treat reading and writing as isolated subjects. They are part of every area. In science, children label parts of a flower. In geography, they write about a country. In art, they describe their pictures.

This cross-curricular integration supports vocabulary, comprehension, and a wider understanding of how language is used.

Children read to learn as much as they learn to read. This broad exposure strengthens literacy in meaningful, lasting ways.

Montessori’s literacy approach is not fast or flashy, but it is thoughtful, intentional, and research-backed. It respects the child’s development, builds real skills step by step, and helps children become joyful, independent readers and writers.

For educators and parents alike, this method offers a clear reminder: when children are trusted, supported, and given the right tools at the right time, literacy grows with ease and delight.